Somewhere in my holiday scrolling through election news on twitter, I came across a tweet from a young person who was not complaining, but not happy either that his mother kept buying him — a gay man — rainbow-themed gifts for Christmas. Not everything, he said, needed to be a LGBTQ gift.

I can’t find that tweet again, but the writer came to mind as I was pondering which “Love is Love” dish towel to purchase at TJ Maxx in the after Christmas sales. My daughter doesn’t even have a kitchen yet. She lives in a dorm. But damn it, there were rainbow dish towels in TJ Maxx and so I was going to buy one.

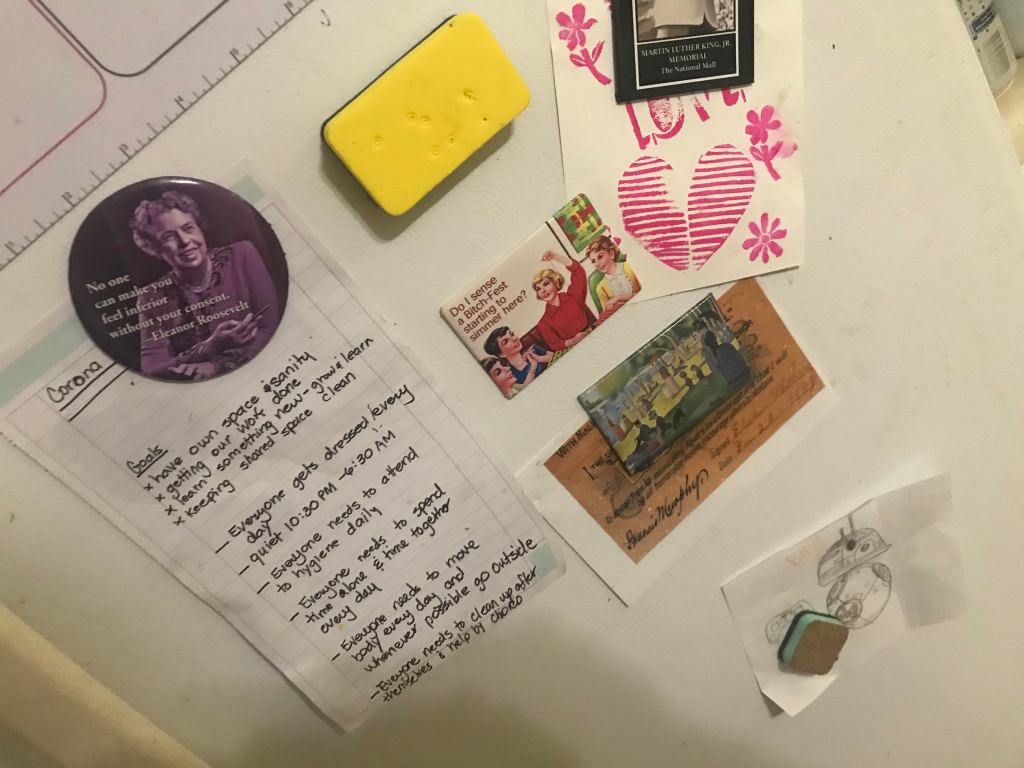

Maybe our children don’t need us to buy all these affirming goods, but maybe we parents of queer children need to buy them anyway. Capitalism and consumption are complicated, but for those of us who have traveled here from a different time — which is just another way of saying that we grew up in the 1980s and before — those dish towels are a symbol of how much better the world is now for LGBT youth.

This Christmas, I also read a lot of takes on The Happiest Season which questioned how realistic it was for Harper to be afraid of coming out to her family. Her justified fear and her father’s reaction seemed like a relic from another time.

The thing is: that’s the era where all of us parents of gay youth grew up. Perhaps in some sophisticated bastions of the 1980s, it was cool to be out. For most of America though, it was dangerous to be a gay youth. No one I knew was out. Those kids who were suspected of being gay were bullied daily and had opposite sex girlfriends or boyfriends as bulwarks of safety. Certainly, not many kids were out to their parents. We knew that we were either gay or straight, and only straightness could be acknowledged. There was no open pondering, no exploration of whether a person might be bisexual or pansexual or any of the possibilities I’ve heard discussed by my daughter and friends as I ferried them around town. The idea that someone might be trans was not even a concept that could be pondered.

In the 1980s, you couldn’t go into any major national retailer to buy Pride merch. Even now, looking back as the hetero woman I am, I don’t have any idea how a person could have acquired a Pride flag prior to 1990. And now I live in a world where Target and Old Navy make demands for my dollars every year so that I can support my lesbian child. I’m happy to shell out my cash.

The “Love is Love” dish towel symbolized the better sleep I get at night, knowing that while my child faced almost endless harassment at school for being a girl (some things never change), she could be safely out at school and home.

Let’s be clear. The world remains a dangerous place for queer youth. I’m not sure that The Happiest Season is so unrealistic. While it’s easier than it was to be out, it’s certainly not easy. LGBT youth face scary bullying and violence across the nation in 2021. Parents still kick their children out of their homes over their sexuality. My daughter has peers who have gone through conversion therapy.

Even as a straight parent, I’m aware that I’m taking a small risk every time I wear my Proud Mom shirt to the store, the library, the body shop.

I don’t know how to express my joy that the risk is smaller than it used to be. Our minds are complex enough to grasp that life can be a lot better, but that we still have a long way to go, right?

Maybe we can buy a dish towel. For straight moms like me, hanging that pride flag or taking a casserole out of the stove with a rainbow oven mitt is part of singing the joy that my child is allowed to be her authentic self. While I worry about her being hurt by bigots — and I do, a lot — I don’t have to worry about her losing her identity. I don’t have to worry about her having to live lies to herself and to me.

For moms like me, we speak our joys in rainbows, and we’re lucky to have children who tolerate us for it.

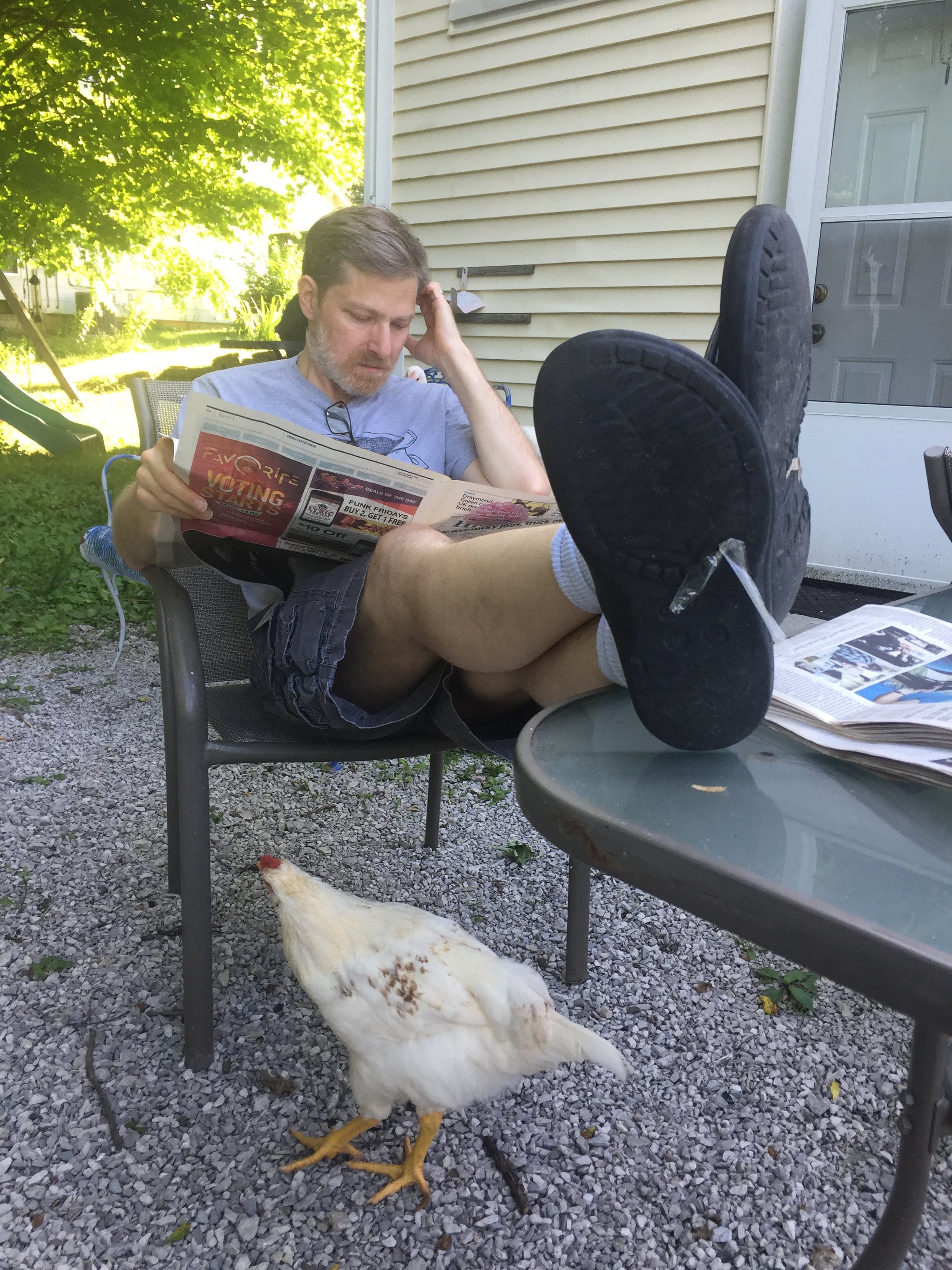

Chickens don’t know about Donald Trump. I can’t stress enough the importance of this fact in my life right now: chickens do not know about Donald Trump.

Chickens don’t know about Donald Trump. I can’t stress enough the importance of this fact in my life right now: chickens do not know about Donald Trump.